“When one thinks how much research in the humanities is based upon… documents that once belonged to private persons or institutions… it can safely be state that detailed provenance research is far more than an innocent pastime for booklovers: it is an essential part of a critical approach to the sources used.”

– Pierre Delsaerdt, Bibliophily and Public-Private Partnership

Provenance refers to the chain of custody of a historical object, the trajectory of its ownership from its creation to the present day. In the world of rare books, documenting a volume’s provenance can often tell us a great deal about the work’s production, distribution, and the ways in which it was read and used. A detailed provenance record can shed light on historical periods and figures, giving us crucial insight into the habits of readers, the popularity of particular works and genres, and the history of the book and book trade. Provenance evidence can also help us determine a rare book’s authenticity, and often adds to the value of the book, particularly if it comes in the form of a signature from a historically important personage.

Book creators, owners, and readers often leave a variety of clues behind that we can use to trace the history of a particular copy. Individuals and institutions mark their ownership in a number of ways, including bookplates (ownership labels, usually pasted inside the front cover), autographs, ink stamps, and so on. In addition, we can frequently learn something about the provenance of a volume through incidental markings, such as marginalia (marginal notes), bookseller price codes, and other inscriptions.

Note hidden in a margin of MSU’s M. Annei Lucani Civilis belli (PA 6478.A2 1515). Note the date, bookseller name, and price.

It’s not always easy to decide which markings are important for determining provenance. Bookplates, autographs, and particularly interesting marginal notes are clearly examples of provenance evidence, even if we don’t know enough at first to decipher them.

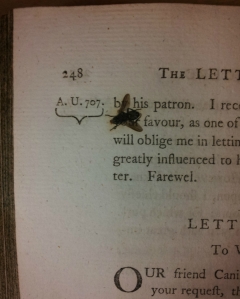

Sometime in the last 214 years, this fly met his unfortunate demise between two pages of MSU’s The letters of Marcus Tullius Cicero (PA6308.E5 M4 1799 v.2). Could this conceivably give us any insight into the book’s provenance? Why or why not?

But what about a seemingly random series of numbers penciled in the margin of the rear pastedown endsheet? What about illegible scribbles or stray marks on a page? When in doubt, should we record everything we see just in case it might mean something? And what about unusual physical features of a book, such as the burned corner of a text block or water-damaged pages? In theory, unique characteristics such as these could help tie a particular volume to a known historical event, providing valuable clues to the book’s ownership history.

In the next post, we’ll be exploring more questions like these, and working through a few examples. In the meantime, leave some comments below. What do you think about provenance? Is it something you had seriously thought about before? What sorts of things do you think are important to record in order to determine a book’s chain of ownership?